As discussed in the first article in this series, physical retail locations are currently experiencing something of an identity crisis. The pressure is on to develop new models that can thrive today and, as has been the case historically, online is regularly cast as the pantomime villain that is “killing the high street” in the national debate.

As anyone visiting (or, as the case may be, not visiting) local high streets up and down the country can probably see, the current proposition for physical retail is far from perfect. It’s in need of reinvention or, at the very least, rapid but intelligently-managed evolution.

But online retail isn’t perfect either. Online needs some kind of physical interface with the customer for it to operate efficiently, or at all even – the customer has to be able to receive the products they order online, after all – and a nationwide network of retail stores located in central, conveniently-accessible areas would seem to offer a logical potential solution, if a currently underperforming and under-optimised one.

So what role could retail have to play in high streets of the future?

Digital high streets?

A common term that pops up when debating this issue is “the digital high street”. Broadly speaking, this tends to cover two main areas.

The first relates to the potential for granting independent/small retailers ecommerce capabilities to enable them to compete digitally (through fast broadband provision or access to shared platforms for example). This is one of those ideas that sounds better than it probably would be in practice – doing so would not likely facilitate some kind of miraculous transformation.

Online is incredibly competitive (both nationally and globally). Independent retailers would then need to compete with large, resource-rich businesses on SEO and ad-word spend as well as needing to handle all the complexity of fulfilling online orders. It’s a reasonable aspiration, but no silver-bullet.

The second, related note expands this point to focus on how high street spaces can evolve to become digitally-relevant. From the retail perspective, this is a very big question – because the really big shift, that many are going to find it hard to adapt to, is that there is a reduced need for stores to overtly ‘sell’ things now because everything is available, with far more choice, convenience and transparency, online.

According to the ONS, it can vary month-to-month but online sales accounted for around 16-18 per cent of total retail in 2018. That doesn’t sound much, but what that data doesn’t cover is the influence that digital has on offline purchases – the research, comparison and reviewing that shoppers carry out in advance of the final purchase.

Retail is already far more digital than the official numbers record and the high street has to adapt to that reality.

Evolving away from “stores”?

Many involved in town planning are looking at the potential for high streets – or “central community spaces” as they might be more accurately considered in this instance – to become more focused on leisure and entertainment, providing people with reasons to visit and spend time there.

It’s easy enough to imagine an idealised (probably pedestrianised and fundamentally restructured) town centre offering live music and other open-air entertainment, various exercise classes, food stalls, children’s rides, etc, but this would likely be at the expense of traditional retail store space – less stores, but better ones is the mantra.

But – this is, to an extent, counter-intuitive. How can retail remain relevant in central community spaces if the endless choice and availability offered by the web translates to a dwindling range in a physical sense? Particularly if those stores are relatively small in terms of floor space, further restricting the number of items they can stock and perhaps having to offer a niche range to compete with the choice online; niche ranges, of course, can only expect to have niche appeal.

This is not to say that traditional, single-retail-brand stores are irrelevant now – some will probably be able to thrive still, depending on their proposition – but stores that are essentially just small rooms stocking a generic store of items, untargeted to any individuals, will become more kitsch.

And this is what we have to remember in all this – technology and the retail systems that facilitate its use are evolving all the time. Physical retail won’t be sorted out tomorrow, but the future direction for retail overall is ever-greater personalisation (moving away from segmentation toward specific individual targeting), in-transit tracking of orders and automation of processes (not an exhaustive list perhaps, but key ones for our purposes here).

Shopper behaviour between channels

So – before we consider what that suggests for future high street models – let’s look at where we are in terms of how offline and online channels work together currently. Data IMRG tracks around delivery and returns is revealing here.

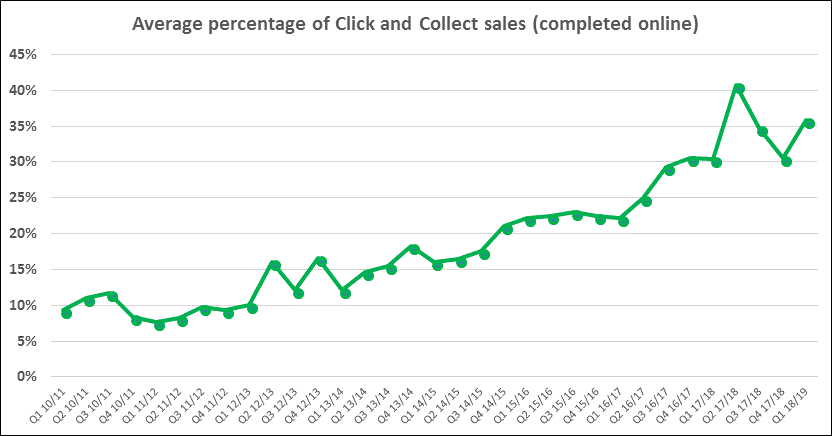

The below graph shows the percentage of online orders for UK multichannel retailers that use click and collect as the fulfilment option:

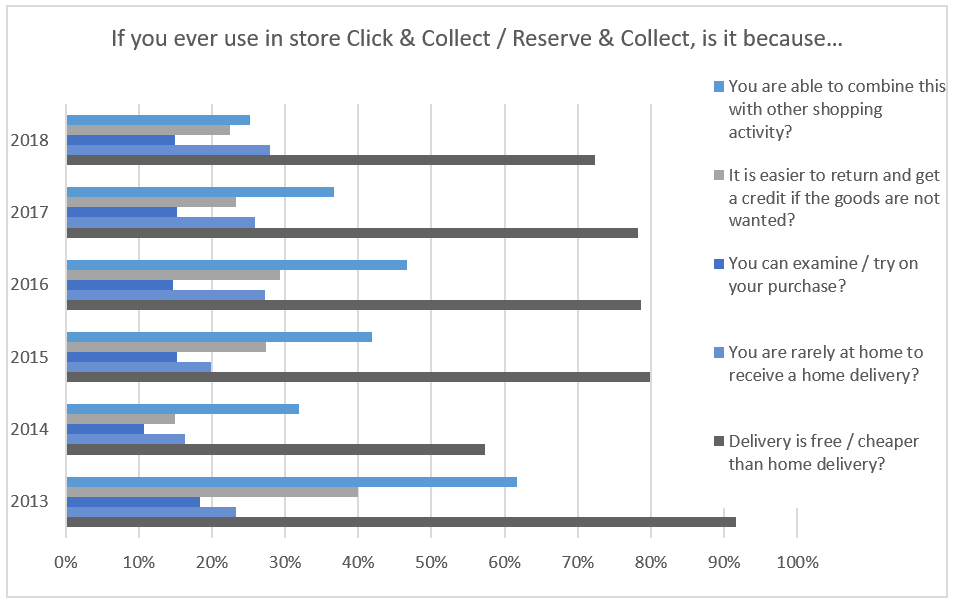

From a reasonably steady beginning back in 2010 (when IMRG started tracking it) the popularity of click and collect has really shot up since 2016 to account for around one in three for multichannel retailers now. One contributing factor to that rise will be the investment that many retailers have made in rolling out the service operationally and promoting its use. If we look at why shoppers say they use click and collect (from our annual consumer delivery review) the reasons are familiar, even if the order of them may be slightly surprising.

While ease and convenience are important, the main reason, by some distance, is actually related to cost. Removing any unnecessary (as the customer would view it, at least) charges and increasing the likelihood of receiving their order, at the first attempt and at their convenience, is seen as important from the customer perspective (points that the report survey results find numerous times).

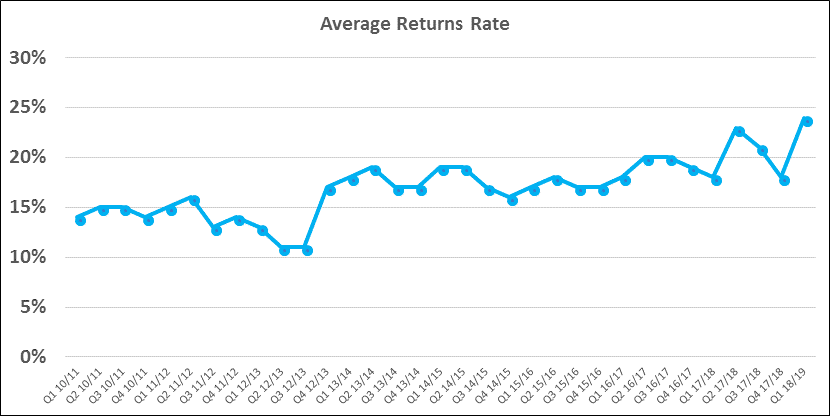

The other area of customer behaviour that has been going up notably recently, causing operational challenges for retailers in the process, is the rate of returns:

This went above 20 per ent last year for the first time since IMRG started tracking it and has remained so in three of the four quarters since. The hike in the return rate is being driven by a range of factors – more retailers offering free returns, widespread use of spend thresholds to qualify for free delivery (ie “spend over £80’” so people order multiple sizes or colours and send some back), the returns infrastructure getting more convenient and more options for returning becoming available.

The rate of return in the above graph is an overall average. When we split the sample by online-only and multichannel retailers, a very interesting picture emerges. For the online-only retailers, their rate is generally far higher than those that have stores. The online-only retailer with the highest percentage of returns, for example, has a rate a full 10 percentage points above the multichannel retailer with the highest rate. Between the online-only and multichannel retailers with the second-highest return rate, there is a 12-percentage-point difference.

The logical conclusion here is that stores must be playing some kind of role in reducing the number of items that are returned. When an item is returned, it also incurs a cost that includes return handling, refurbishment, inspection, repackaging and disposal, often as a discounted price and in the case of ‘free returns’ the retailer also pays the carriage cost.

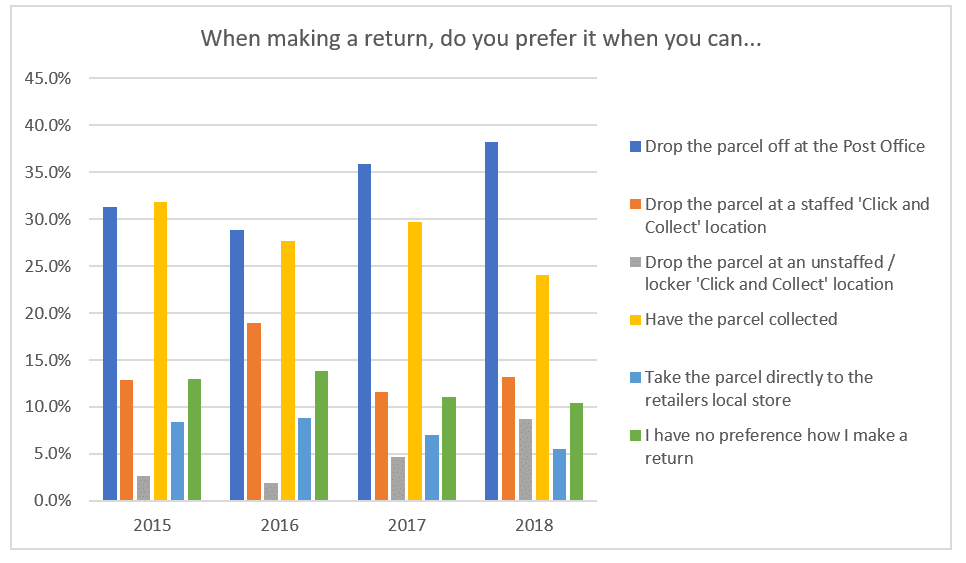

As the below chart from our annual consumer delivery review shows, shoppers’ preferred options for returning parcels are to drop the parcels off, either at a Post Office, click & collect location or the retailer’s store. Collection has, meanwhile, actually declined over the past few years because it invariably requires the customer to be at home.

What this data suggests is that shoppers do seem comfortable with using offline and online in combination – buying or reserving online, collecting and returning to physical locations. The logical limitations around how much they will use these physical retail locations will be related to where and when they can do it, as well as how convenient and engaging the process is.

Online vs offline experiences

The influence, then, of digital on physical retail is already strong and only likely to increase.

While with traditional retail a large store was seen as a positive, as it enabled that retail location to offer a greater variety of choice, modern retail is moving toward a model where the customer doesn’t need to be presented with endless choice – they are instead connected purely to items of relevance, interest and appeal to them specifically.

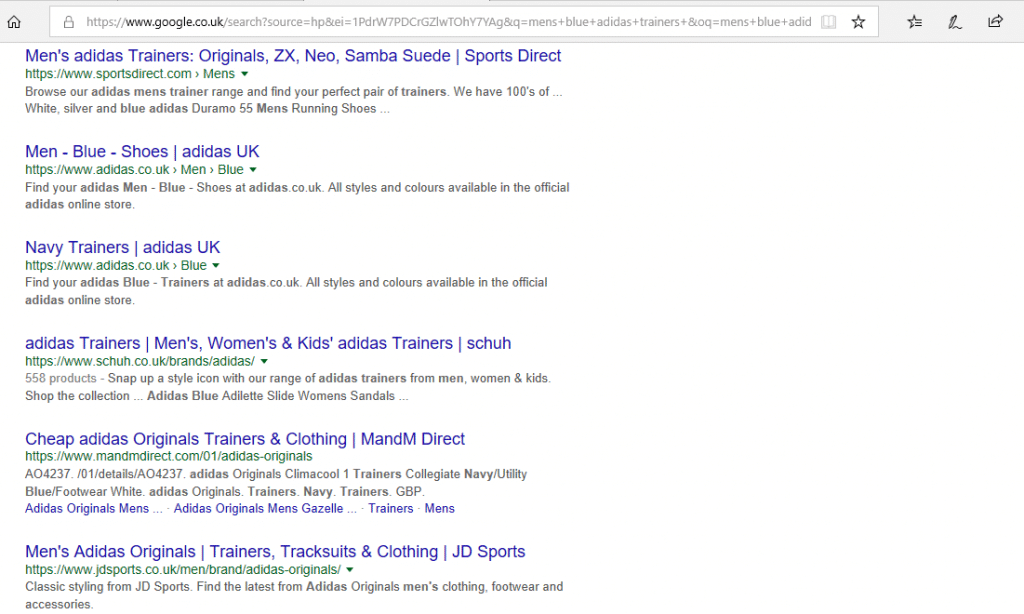

Currently, online shopping journeys and the offline equivalent are poles apart. To illustrate how far, consider the Google homepage. This is the starting point for many web users. A decade or so ago there was a tendency for users to execute very basic search terms, which in a retail sense would often mean typing in the name of the retailer with whom they wanted to shop (“John Lewis”, “Tesco” etc). Since then, search behaviour has evolved so that terms have become much more complex and specific and focused on the item they are ultimately trying to find (eg “male blue Adidas trainers”).

In these online shopping journeys, the user is immediately confronted with multiple options (endless even, given the above example returned 287,000,000 results), some of whom they may never have heard of before. On the high street, the only real option is to start with a specific retailer by entering a shop (as was typically the case with the ‘old’ Google search term behaviour) – so the shopper will have to make a decision on the retailer first, from a static list, then try to find the “male blue Adidas trainers” once in there.

In short, the experience on the high street lags behind that of online by around a decade. It is out-of-date with modern customer expectation because stores are often rigidly restrictive in being single-retailer-specific – which means a physical space that only serves up products specific to that retailer – whereas the way that many people use the web makes it brand-agnostic by default.

That is the most evident current schism between online and offline experiences.

Bridging the experience gap

In a physical sense, access to full choice and availability – which is the promise of the web – has to be mapped onto the connection of individual to thing, by removing the various physical barriers and restrictions inherent to the existing infrastructure.

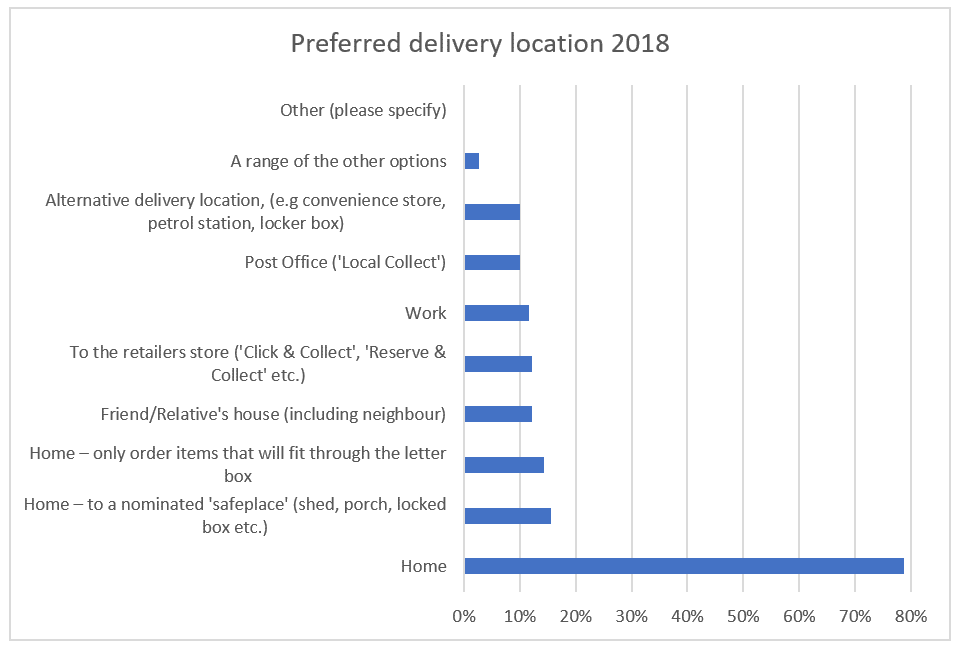

Generally speaking, there are two options for how orders can be fulfilled – it can either be delivered to the customer (at their home, office etc) or they have to come out to retrieve it from a collection point (store, locker etc).

In the UK, we have a culture of expectation around home delivery; almost 80 per cent of respondents to our annual consumer delivery review said they tend to select that option.

In order for the offline experience to match the online experience, the customer cannot be restricted by geography. At the moment, the physical retail space in proximity to some shoppers might only present them with a small number of stores, greatly limiting which brands they can collect from. Some have click and collect deals in place with other retailers (eBay and Argos for example), but these still tend to offer only a fraction of what is available online across all brands.

There are a few options available for how shoppers can be enabled to collect and return anything, anywhere.

The most obvious solution would be to adapt the existing infrastructure (i.e. rows of single-retail-brand stores) by switching on completely brand-agnostic click and collect and returns capabilities in a suitable proportion of them. A limitation here would be around competition – could retailers allow customers to pick up stock from rival brands, which would also need to be hosted within their stock rooms; and would every store become too “samey”? Many may also have issues with finding space for click and collect parcel storage, or installing changing facilities (necessary for reducing online return rates and improving operational efficiency).

An alternative would be to develop a nationwide network of spaces (there is no shortage of empty stores across the country) to redesign and repurpose them from the ground-up, as publicly-accessible fulfilment and returns inventory depots. The exact layout and structure could vary depending on the floor space available:

- If small, different stores could focus on a product category. So if it offered changing rooms and mirrors, it could be specific to things like fashion and footwear. Others could host a category of electrical equipment (consoles, TVs, smartphones) for testing and trialling.

- If larger, some could function as showrooms for home products, offering the potential for laying out furniture for trying before purchasing and getting delivered to home.

- If a very large space, the scope becomes a lot bigger and many of these types of inventory depots could be included within that single location; making them more like shopping centres, but with the inventory carried at any given time far more personalised in relation to the visitors.

- There is also potential for using these locations as forward-stock spaces, offering local same-day / specified time-slot delivery at an affordable price; particularly should automated vehicles and drone usage become a reality in fulfilment. While this wouldn’t bring those customers to the high street necessarily, it would still add a valuable revenue stream and service option to the outlet.

All this – as in a vision of physical retail as inventory hub – may sound a little underwhelming from the perspective of retail theatre. Yet technology already exists to make them far more engaging than they sound – virtual displays, augmented reality, building entertainment and shopper experiences around browsing and collecting / returning. Digital technology makes it possible to display anything anywhere, but only actually move and store a much smaller number of physical items.

Another option would be for mobile units to bring orders to areas that do not have proximity to central high street locations, using in-transit communications to keep shoppers up-to-date as to when their stock is nearby, perhaps visiting commercial estates for example. If they were able to offer changing facilities as well, it would be able to perform the role of brand-agnostic store. Again this may sound fanciful, but Amazon already do something very similar with their Treasure Truck.

The solution isn’t likely to be one or the other, but a combination working in tandem. Other solutions not covered above may also have a role to play, but the general principle is that orders should be consolidated at a place of maximum convenience to encourage shopper usage – and that access has to become more brand-agnostic through these solutions to mirror the choice and availability of online.

That is what would make sense from the customer perspective and, although it represents a fairly fundamental shift for how retail works at present, retail is supposed to be all about the customer.

Online purchasing – or just shopping?

As a concept, retail has, and always will, refer to the process of getting manufactured goods into the hands of individuals. As long as the physical infrastructure is assisting with that, it’s still retail.

The connection of individual to thing is the crucial stage of the process. When someone buys something online, although a single selection has ultimately been made, the shopper has not actually felt or tried on the product. Although a payment is quite often taken at that stage of the online order, all the customer has done essentially is browse through entries in a catalogue – such is the nature of distance-selling. It is that point of collection that confirms the final purchase decision.

While this article has focused on how physical retail could evolve from the customer perspective, next week’s article looks more at business efficiency – in particular how physical retail can help to mitigate the environmental impact of online retail, which has become such a pressing issue over the past 12 months.

Andy Mulcahy is Strategy and Insight Director and IMRG and Andrew Starkey is Head of e-Logistics at IMRG.

Click here to sign up to Retail Gazette‘s free daily email newsletter