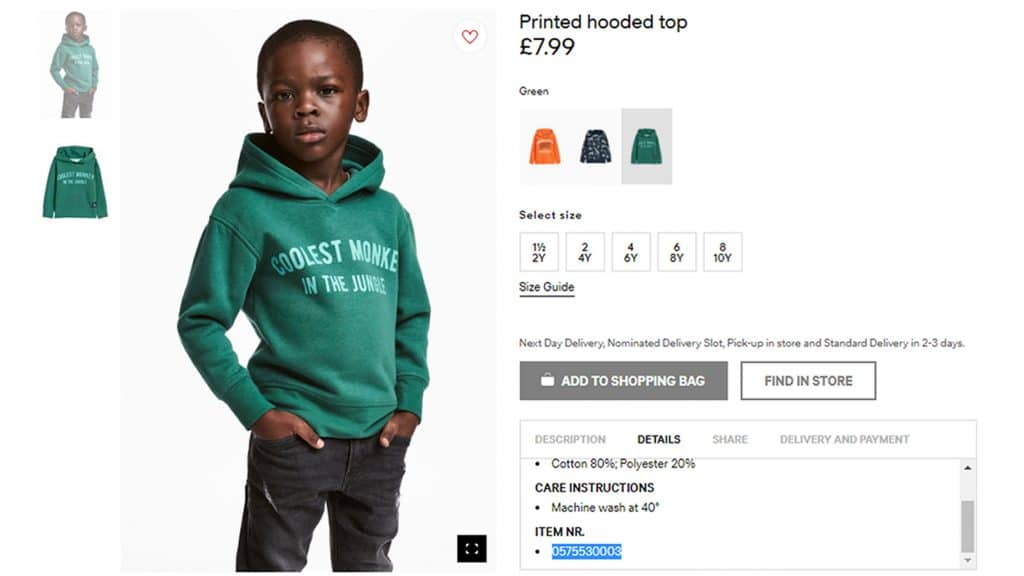

“As far as this racist H&M ad, the people of the H&M company knew exactly what they were doing and they anticipated the backlash. This is their coded way of tapping into the white supremacist demographic. Racists buy clothes too, and these companies want those bigoted dollars.”

When H&M’s “coolest monkey in the jungle” advert was first brought to the attention of the masses on Twitter, the original post was shared 14,000 times within a day.

The subsequent backlash didn’t take long to transfer from Twitter to the wider world. The young model’s parents were soon being interviewed on morning TV, celebrities from P. Diddy to Lebron James were weighing in on the debate, and H&M stores were being ransacked in South Africa.

Marketing mistakes are nothing new, and it’s plain to see that even retailers the size of H&M with marketing budgets the size of a small country’s GDP can still slip up.

Yet, in our social media age the ferocity, scale and impact of the backlash when something goes wrong is reaching unprecedented levels.

With marketing spanning multiple channels that are pumping out content 24 hours a day, brands are reaching more people than ever. Unfortunately, the more people who are familiar with a brand, the harder the fall when a misjudgment is made.

“The range of marketing activity for retailers spans a host of channels; so the opportunity for things to go wrong can be significant,” Conran Design Group chief executive Thom Newton told the Retail Gazette.

“In TV advertising – as an example – while the intention of the ‘big idea’ might be good, how it is interpreted by the viewer can’t always be guaranteed.

“The range of marketing activity for retailers spans a host of channels; so the opportunity for things to go wrong can be significant”

“Tesco’s message in its ‘all are welcome’ Christmas 2017 TV campaign divided consumers and Sainsbury’s ‘trenches’ ad in 2014, received a huge backlash for apparently using WW1 to flog more turkeys.”

But what effect does this really have on a retailer? Boycotts of brands are declared on Twitter every day, and public backlashes have largely become commonplace on social media, but do these translate to a real-world effect on margins?

In 2013, Abercrombie & Fitch’s chief executive Mike Jefferies sparked outrage by saying his brand hired “good-looking people in our stores, because good-looking people attract other good-looking people”.

He unwisely continued along this train of thought, adding: “A lot of people don’t belong, and they can’t belong. Are we exclusionary? Absolutely.”

This of course sparked a media storm, but according to 3radical chief marketing officer David Newbury, it may have also contributed to its dive in sales, which has largely continued ever since.

“It is very difficult to pinpoint what direct impact this had on Abercrombie’s commercial performance but when you look at the results, profits declined 77 per cent percent that year, with some of their key stores showing consecutive sales decline for the next two years, it is hard not to relate the two factors,” Newbury said.

“Who would want to take that kind of risk?”

Although these media storms can be incredibly fierce, like many new media phenomena they are often short-lived and seemingly transient.

However, with this new media comes a new generation of consumers with a new set of expectations from the brands they buy from.

READ MORE:

Having grown up with the technology, they’re also more than proficient enough with it to understand that every outraged post, unsatisfactory apology and piece of damage limitation leaves a digital footprint.

This is where the real damage to a brand can be done, according to Bazaarvoice marketing vice president Sophie Light-Wilkinson.

“It causes long lasting damage because of the online footprint that leaves, it’s not something that’s just a flash in the pan it can have quite a lot of legacy,” she said.

“Generation Z is becoming very influential. By 2020 they are going to become the biggest group of consumers globally. They’ll have about 40 per cent of purchase power and they are very socially conscious because of the far reaching global events that they have lived through.

“More so for them, they are looking at socially responsible brands and retailers. If you have damaging marketing campaigns and then that legacy, it’s not just going to have an impact on sales today it’s going to have an effect on future sales because of that impact and influence it’ll have on that new group of consumers that are getting more and more powerful.”

Does the digital age do away with the age-old adage “any press is good press”? If thousands of people are debating whether a brand should be chastised or celebrated, it’s reasonable to assume the many of them will have visited the brand’s site, or at least their social pages. Higher traffic is often in line with higher sales.

When Urban Outfitters revealed their “Kent State University” jumpers complete with fake blood spatters, it wasn’t long until people realised Kent State was the scene of a mass shooting in the 1970s.

People were outraged by this move, but such an obviously offensive stunt could have simply been a marketing ploy.

“If the resultant press and social media coverage offsets any potential damage the retailer may suffer from a negative backlash, then ultimately the ‘net’ commercial impact may well be positive”

“Outraged people took to social media and the story was covered in the global media and yet the brand escaped long-term damage; lending weight to the theory that ‘controversy’ can simply be part of a successful marketing campaign,” Newton said.

“If the resultant press and social media coverage offsets any potential damage the retailer may suffer from a negative backlash, then ultimately the ‘net’ commercial impact may well be positive.

“But this is a dangerous game to play and one which can’t be played too often.”

Dangerous games are often the ones with the biggest rewards. Advertisers have long known the power of controversy, and it has driven movements from rock’n’roll to punk.

Poundland’s recent “elf behaving badly” campaign rattled some cages, but largely proved successful for the discount retailer, gaining it substantial popularity and a reputation as a brand with a sense of humour.

Although a skilled marketing team can utilise the power of provocation, but professor of marketing at Edinburgh Business School Stephen Carter says that the same new generations have made it far more difficult to succeed.

“In the history of advertising there has always been the controversial,” he said.

“Again, it depends on the receiver of the message. For example, 10-15 years ago it was quite easy to predict which socio-demographic or lifestyle segment would respond to controversial advertising.

“But today, with the rise and rise of the millennial generation, within which there are multiple segments – for example, the ‘hip-ennials’ and the ‘old school millennials’ – it is increasingly becoming difficult to gauge who exactly would respond to these type of adverts.”

Though new technology and a new audience have provided greater potential reach than ever before for retailers, they have also created a more complex environment.

It may be far harder to predict the outcome of a risque marketing move, but they are still the ones that stick, for better or for worse.

Click here to sign up to Retail Gazette’s free daily email newsletter